History is full of grand battles and famous kings, but hidden in its shadows are stories so shocking they can unsettle even seasoned historians.

Few recall that a Roman emperor once staged 735 bloody games and forced the disabled to fight to the death, or that the shortest war ever ended in just 38 minutes.

Even more astonishing, Spain’s Philip II once signed an edict sentencing the entire population of the Netherlands to death, while a Persian vizier traveled with a library carried by 400 camels.

Add to this Qin Shi Huang’s fiery purge of books and the strange tally of only three German empires in a thousand years, and history reveals a darker, stranger side than textbooks ever suggest.

The Roman emperor Commodus once gathered all the disabled people in the Colosseum and forced them to fight to the death

When Commodus ascended the Roman throne in 180 AD, the empire inherited not a statesman, but a showman. Born in 161 AD, the son of Marcus Aurelius, he reigned until 192 AD and gained infamy as one of Rome’s most eccentric rulers.

Commodus was obsessed with self-glorification. He demanded to be worshiped as Hercules, son of Jupiter, and even renamed the months of the year after his own titles: Commodus, Augustus, Amazonius, Invictus. In 190 AD, he went further, ordering Rome itself to be renamed Colonia Commodiana. None dared oppose his delusions.

More disturbingly, Commodus loved to fight as a gladiator. He personally entered the arena, slaying wild beasts with a bow or sword, and staged contests that demeaned the dignity of the empire. Historical accounts say he organized 735 gladiatorial games, forcing citizens to participate. For him, the arena was both theater and purge.

His cruelty climaxed in a shocking decree: all Rome’s “imperfect” citizens—dwarfs, the disabled, and the mentally ill—were rounded up and driven into the Colosseum. There, they were compelled to fight each other to the death for the amusement of the emperor and the masses. To Commodus, such spectacles cleansed Rome of weakness and affirmed his divine power.

His reign of excess ended in 192 AD, when conspirators strangled him in his bath. Yet the memory of Commodus lives on: a ruler who renamed an empire after himself, staged hundreds of deadly games, and turned the world’s greatest arena into a slaughterhouse of the vulnerable.

The Shortest War in History: Britain vs. Zanzibar in Just 38 Minutes (1896)

At dawn on 27 August 1896, the island of Zanzibar became the stage for the shortest war in recorded history—lasting just 38 minutes. The conflict ignited when Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini died suddenly on 25 August, and his cousin Khalid bin Barghash seized the palace without British approval. Britain, which had turned Zanzibar into a protectorate in 1890, refused to recognize him, demanding instead that Hamoud bin Mohammed be installed.

When Khalid ignored an ultimatum to abdicate, the Royal Navy mobilized. By 9:00 a.m., five warships—HMS St George, HMS Philomel, HMS Racoon, HMS Thrush, and HMS Sparrow—lined up in the harbor. Khalid’s forces, numbering around 2,800–3,000 men, fortified the palace with artillery and a small yacht, the Glasgow, as his naval defense.

At 9:02 a.m., the British opened fire. Within minutes, palace guns were silenced, the Glasgow was sunk, and fires consumed the royal complex. By 9:40 a.m., Khalid had fled to the German consulate, leaving behind over 500 casualties among his troops. British forces suffered just one wounded sailor.

The war ended with the Union Jack raised over the Sultan’s palace. Hamoud bin Mohammed was installed as a pro-British ruler, marking the consolidation of Britain’s control over Zanzibar.

Though brief, the war was a brutal reminder of imperial dominance: five modern ships and 38 minutes were all it took for the world’s strongest empire to topple a sultanate.

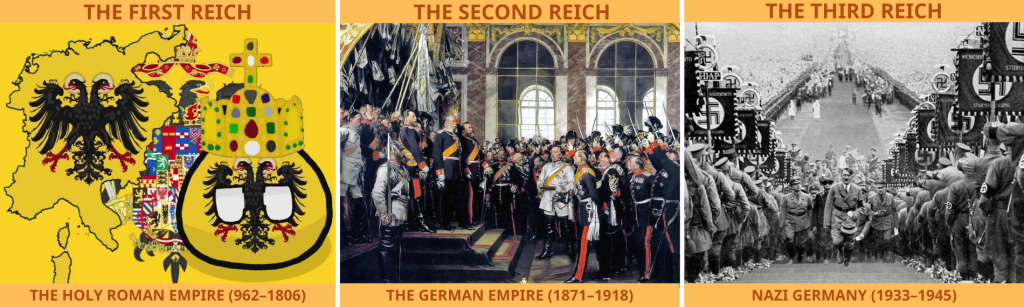

Only Three German Empires in a Thousand Years of History

Germany, unlike Rome or China, has known only three empires in its long history, each shaping Europe in turn.

The first was the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806), born when Otto I was crowned emperor in Rome. Far from a centralized state, it was a loose confederation of duchies, bishoprics, and free cities stretching across modern Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and northern Italy. For nearly 850 years, emperors like Frederick Barbarossa and Charles V struggled to balance papal power, rebellious princes, and the dream of a united Christendom. Its decline culminated in 1806, when Napoleon forced Emperor Francis II to abdicate.

The second empire—the German Reich of 1871–1918—was the creation of Otto von Bismarck. Forged through wars against Denmark, Austria, and France, it united the German states under Prussian leadership. Proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles in January 1871, it produced Europe’s strongest industrial and military power. Yet Wilhelm II’s imperial ambitions dragged Germany into World War I, ending in defeat, revolution, and abdication in November 1918.

The third and darkest empire was the Third Reich (1933–1945) under Adolf Hitler. Born from the ashes of the Weimar Republic, it promised revival but delivered dictatorship, genocide, and global war. Hitler declared it would last “a thousand years”; instead, it collapsed in 12, leaving Europe in ruins and millions dead.

Three empires in a millennium—rising, uniting, and destroying—each marked Germany’s struggle between grandeur and catastrophe, leaving legacies that still shape Europe today.

The Spanish Inquisition and the Death Sentence on the Entire Netherlands (1568)

On 16 February 1568, King Philip II of Spain issued one of the most shocking edicts in European history: the condemnation of an entire people. By his decree, every man, woman, and child in the Netherlands was sentenced to death for heresy.

The roots lay in Philip’s fierce Catholic orthodoxy and his determination to crush the Protestant Reformation spreading across his provinces. The Inquisition had already claimed thousands of lives, but the Netherlands—wealthy, independent-minded, and increasingly Calvinist—posed a unique challenge. To enforce conformity, Philip relied on Spanish governors and tribunals. In the years leading up to 1568, over 1,800 nobles were executed for defying his rule, while thousands of commoners faced torture, exile, or confiscation of property.

The 1568 edict, though impossible to carry out literally, symbolized the king’s ruthless intent: collective punishment to terrorize a population of nearly 3 million. Resistance soon coalesced under leaders like William of Orange, sparking the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648). What began as an Inquisition writ turned into a full-scale revolt that would eventually secure Dutch independence.

The decree also revealed the limits of absolutism. Even the most powerful monarch in Europe could not annihilate an entire nation. Instead, Philip’s overreach inflamed rebellion, bankrupted Spain, and transformed the Netherlands into a beacon of resistance.

Thus, the Inquisition’s darkest hour in the Low Countries birthed the long struggle for Dutch freedom—proof that tyranny, when pushed to extremes, sows the seeds of its own defeat.

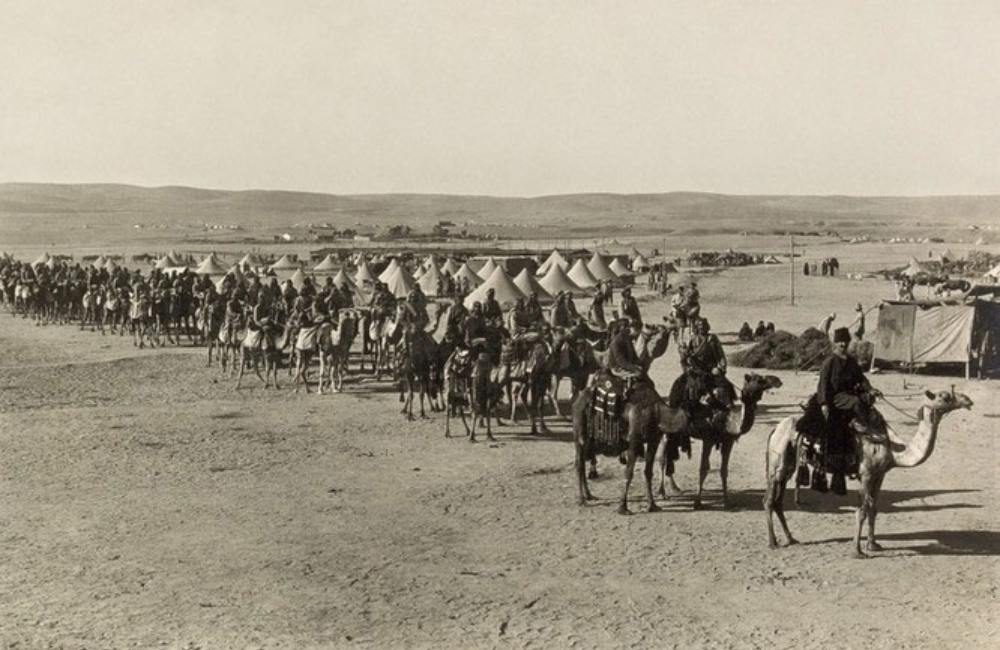

Sahib Ibn Abbad – The Persian Vizier Who Traveled with a Library on 400 Camels

In the golden age of Persian culture, one man’s devotion to knowledge became legendary. Sahib Ibn Abbad (938–995), vizier of the Buyid dynasty, was not only a statesman but also one of the era’s greatest scholars and patrons of literature.

Born in Rayy (near modern Tehran), Ibn Abbad mastered Arabic, Persian, theology, philosophy, and poetry. His brilliance made him indispensable to two Buyid rulers, under whom he served as vizier for over 18 years. Yet what set him apart was not merely his governance but his unparalleled library. Wherever he went, his books followed—transported by 400 camels. Of these, 60 camels were needed just to carry dictionaries. His caravan of learning symbolized his conviction that no decision, political or personal, should be made without wisdom at hand.

Ibn Abbad turned his court into a center of scholarship. Poets, theologians, and scientists found patronage under his protection. He championed Mu‘tazilite theology, wrote treatises on language and law, and corresponded with intellectuals across the Islamic world. His generosity made him a cultural icon, remembered for elevating learning as both a personal pursuit and a pillar of statecraft.

When he died in 995, Sahib Ibn Abbad left no empire of land or armies but a legacy of intellect. His name endures in chronicles as the vizier who valued books more than treasures, proving that in an age of power struggles, knowledge itself could be the greatest weapon.

Qin Shi Huang’s Book Burning and the Execution of Scholars (213–212 BC)

In the early years of China’s first empire, Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BC) sought not only to unify lands but to control thought itself. After conquering rival states in 221 BC, he standardized weights, measures, coins, and script. Yet in 213 BC, fearing dissent from scholars loyal to old traditions, he ordered one of history’s most infamous purges: the Burning of the Books.

The decree banned all texts outside practical use—medicine, agriculture, and Qin’s own chronicles. The revered Five Classics of Confucianism were proscribed, erased from private libraries. In 212 BC, the crackdown deepened: more than 460 Confucian scholars were arrested and executed, buried alive according to traditional accounts, for defying imperial control.

The emperor’s aim was clear—obliterate the intellectual foundations of rival schools and cement Qin Legalism as the sole doctrine of the realm. His chancellor Li Si justified the policy as essential to unity: “If the people follow multiple teachings, they will never obey.”

Yet the destruction was never total. Copies hidden in scholars’ homes and preserved within the imperial archive allowed Confucian texts to survive into the Han dynasty, where they were revived as state orthodoxy. Ironically, the attempt to erase them ensured their fame, as later generations condemned Qin’s tyranny while venerating the works he tried to destroy.

Qin Shi Huang’s empire collapsed within 15 years of its founding, but the memory of fire and blood in 213–212 BC endures as a warning: the power to rule may conquer armies and walls, but it cannot forever silence ideas.