In 1587, more than one hundred English men, women, and children set foot on Roanoke Island, off the coast of present-day North Carolina. This group, led by Governor John White, was not the first to try their luck there, but they were determined to succeed where others had failed. Among them was Virginia Dare, the first English child born on American soil, a symbol of hope for England’s new world ambitions.

Shortly after establishing the colony, White sailed back to England for supplies. He expected to return within months, but fate intervened. The Anglo-Spanish War erupted, and England’s navy was consumed by the looming threat of the Spanish Armada. White’s pleas for ships were delayed, forcing him to wait three long years before setting sail back to Roanoke.

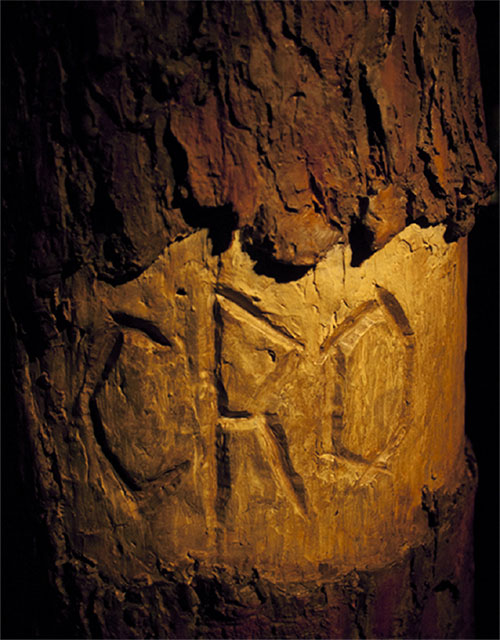

When he finally returned in 1590, the colony he had left bustling with life was eerily silent. The houses were dismantled, not destroyed, and no bodies or signs of violence remained. The only trace was a single word carved into a wooden post: “CROATOAN.” Another carving, “CRO,” was etched into a nearby tree. To White, this meant the settlers had relocated to Croatoan Island, home to a friendly Native American tribe. Yet storms and dwindling supplies prevented him from investigating further. White returned to England, never to see the settlers—or his own daughter and granddaughter—again. Thus began one of America’s greatest unsolved mysteries: the disappearance of the Roanoke Colony.

The main theories about the disappearance

The fate of the colonists has fueled centuries of speculation. The most enduring theory is assimilation. Archaeological finds on Hatteras Island, once known as Croatoan, reveal English pottery, a signet ring, and even blacksmith remnants from the late 1500s. These suggest the settlers integrated with the Croatoan tribe, marrying and sharing lives with them. Later explorers, such as John Lawson, claimed to encounter Native Americans with blue eyes and knowledge of “speaking out of a book,” hinting at English ancestry.

Yet assimilation is not the only theory. Some believe the settlers were massacred by hostile tribes, a story that surfaced decades later among Jamestown colonists. Others argue starvation and disease, driven by environmental collapse, forced their demise. Scientific evidence lends weight here: tree-ring studies reveal that between 1587 and 1589, the region experienced the most severe drought in 800 years. Food would have been scarce, both for colonists and local tribes.

A darker speculation involves Spanish forces. At the time, Spain fiercely opposed English expansion. Some suggest Spanish soldiers from Florida destroyed the settlement, though no direct evidence survives. Another theory is that desperate colonists attempted to sail back to England themselves, only to vanish at sea.

Each theory holds fragments of plausibility. None fully explains the colonists’ fate. Like puzzle pieces scattered in time, they whisper possible truths yet leave the heart of the mystery unsolved.

Archaeological and historical evidence

Clues to Roanoke’s fate rest not in ghostly tales, but in artifacts buried in the soil. Excavations on Hatteras Island have uncovered 16th-century English goods: fragments of pottery, tools, and even a sword hilt. These items, found alongside Native American artifacts, point to cultural blending. Such evidence strengthens the case that at least some colonists lived among the Croatoan tribe.

Historical records add further intrigue. Captain John Smith, the leader of the Jamestown colony, reported hearing of Europeans living inland with Native tribes. Later, John Lawson described locals who claimed descent from “white ancestors” and displayed striking European traits. While tantalizing, these accounts remain second-hand, blurred by time and cultural misunderstandings.

Nature also played its role. Dendrochronology—the study of tree rings—confirms that the Roanoke settlers arrived during a catastrophic drought. Crops would have failed, and survival would have demanded alliances or migration. Without reliable food supplies, the colonists may have had little choice but to abandon their fragile outpost.

Curiously, no graves or mass killings have been unearthed on Roanoke Island itself. The dismantled buildings suggest a deliberate, organized departure rather than sudden catastrophe. This absence of violence has shifted most scholarly support toward relocation rather than annihilation.

Yet despite centuries of digs, DNA testing, and soil analysis, the evidence remains frustratingly incomplete. Roanoke is a puzzle that resists closure, teasing us with fragments that never quite form a whole.

Why is it called the “Lost Colony”?

The colony’s very name—the Lost Colony—was born from the silence that greeted John White in 1590. One hundred and seventeen souls, including families and children, had vanished. Without graves, bones, or battle remains, their disappearance defied the expectations of the age. Unlike other failed colonies where death left clear scars, Roanoke left only absence.

The word “lost” speaks less to their physical fate and more to history’s inability to trace them. The colonists may have survived by joining Native tribes, but they were “lost” to England’s records, their names never entered into genealogies or returned across the Atlantic. For the English Crown, eager to plant its flag in the New World, this vanishing was both a political and emotional blow.

Over time, the name solidified into legend. The image of an entire colony disappearing into the wilderness gripped imaginations. Schoolbooks carried the story, and folklore embellished it. Roanoke became less a historical event and more a symbol: of mystery, of cultural clash, of the fragility of human ambition against untamed lands.

What makes it haunting is not just what happened, but what did not happen: no distress signal, no wreckage, no final testimony. Just the silent letters CROATOAN. In that silence, the colony became forever “lost”—to their families, to their nation, and to the certainties of history.

Myths versus historical reality

As the centuries passed, Roanoke’s disappearance morphed from history into legend. Writers and storytellers spoke of colonists who “evaporated,” vanishing as if swallowed by the wilderness. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Gothic novels and pulp magazines amplified the tale, casting it in supernatural tones. Some imagined ghostly apparitions, curses, or even alien abductions in modern retellings.

But history tells a calmer, though no less compelling, story. The dismantled houses show planning, not panic. The absence of a Maltese cross—meant to signal danger—suggests the settlers left willingly. Archaeological evidence points to relocation and integration with Native tribes rather than a sudden disappearance. The “evaporation” myth persists because of the profound human need for closure. Where facts end, imagination rushes in.

Still, myths have power. They keep the mystery alive, carrying Roanoke into popular culture. The carved word CROATOAN appears in television shows, horror stories, and even as the last word of writer Edgar Allan Poe before his death, further fueling intrigue.

Separating myth from reality allows us to appreciate both: the settlers’ real struggles with famine, politics, and survival, and the cultural fascination with mysteries that defy explanation. Roanoke is not just a lost colony—it is a story America tells itself about uncertainty, survival, and the shadows of history.

The ongoing search for answers

The search for Roanoke’s fate has not ended with dusty archives. Modern archaeology continues to probe Hatteras Island and sites near Albemarle Sound. In recent decades, digs have unearthed 16th-century European artifacts, including blacksmithing remnants known as “hammer scale,” suggesting English technology at work alongside Native crafts.

Genetic studies have also sought traces of English lineage among Native American populations in the region. While no definitive link has been proven, oral histories and family traditions hint at deep interweaving of cultures. Each new discovery narrows the possibilities but never closes the case.

What keeps the search alive is more than academic curiosity. Roanoke stands as a symbol of endurance and enigma. Every artifact found is a whisper from the past, a reminder that history hides as much as it reveals. Researchers, both professional and amateur, continue to walk the sandy shores, sift the soil, and piece together clues.

For now, the colony remains a riddle. Perhaps one day, new technology—DNA breakthroughs, satellite imaging, or yet-uncovered documents—will provide the final answer. Until then, Roanoke endures not just as a historical mystery, but as a legend that bridges the known and the unknown. It is America’s oldest unsolved story, still echoing through the carved letters of CROATOAN, still calling to us across centuries.